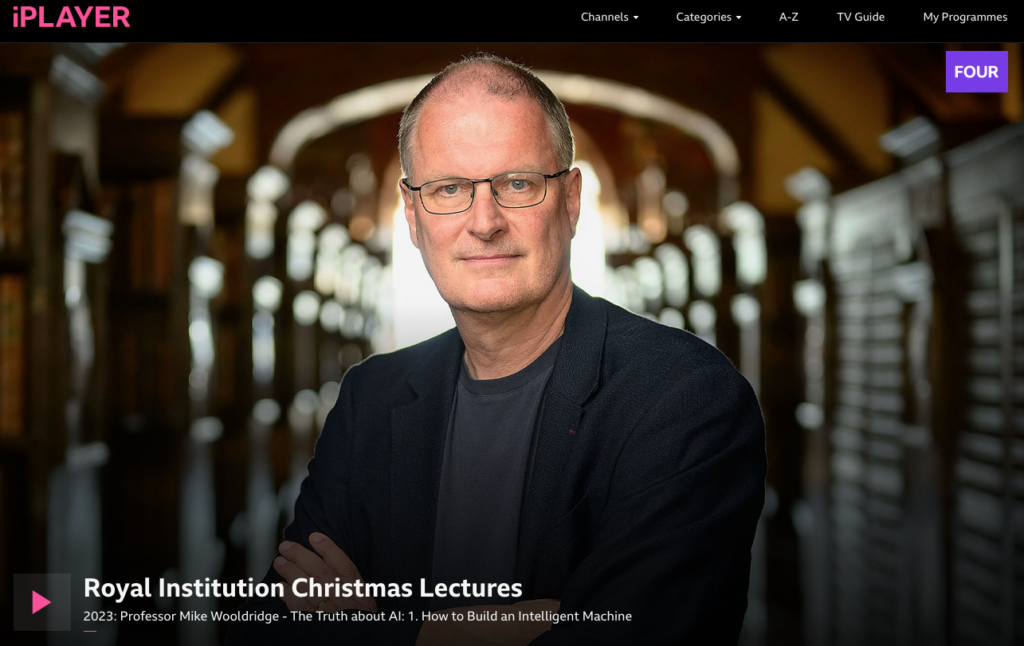

It was an honour to be invited to attend the 43rd Annual Conference of the British Computer Society’s Specialist Group on Artificial Intelligence earlier this month. I was invited to take part in a panel discussion with Prof. John Naughton, Prof. John Stevens and Dr. Giovanna Martinez. Here’s the rough text of my opening contribution:

As my biography notes, apart from some brief undergraduate studies, I have no technical expertise in the field of Artificial Intelligence, so I have a deep respect for many of you here who are indeed experts in your field and have been pioneering this science long before it was vogue.

I believe it’s now uncontroversial to argue that this field needs to become multi-disciplinary, such is the potential impact of new technologies on society. Though, I suspect at this stage you may need some convincing of the value of Christian theology within the conversation.

What does it mean to be human? What is the purpose of work? How can I build an ethical framework? How can society flourish? What is a compelling vision for the future?

These are the kind of high-level questions that AI pioneers are beginning to ask, or if not, should be asking. They are also questions that theologians have been pondering for hundreds of years.

Christians have been at the forefront of societal revolutions in the past; they have been artists and authors, musicians and medics, and of course scientists. They have often helped to build the structures to support revolutions; committed to education, health services and care of the vulnerable. Earlier today some of you went on the ‘walking tour’ – try and walk 100m in Cambridge without seeing the revolution that is Christianity at work – as historian Tom Holland notes, we are inescapably “Christian”.

The AI revolution is incredibly powerful – so what countervailing power will keep it on track? What will make it good?

In recent weeks we’ve seen that neither nation states nor large tech companies have all the resources to manage this well. Do we have confidence that OpenAI or indeed Rishi Sunak are working for the good of all. Will a board of trustees, state regulation or global treaties be enough to ensure a good outcome?

I would contend that Christian theology offers a more robust countervailing power than these, because it is unswervingly committed to human flourishing over and above self-interest.

You’ve no doubt seen ‘The Trolley Problem’ – there’s a runaway tram heading down a track with a fork in it. The tram is about the kill 5 people on the track, or if you pull the points lever just one person will die. The ethical dilemmas become more complex but are essentially they’re asking two questions; 1) Should I intervene by pulling the lever or doing nothing? 2) Which outcome is the least worst?

It’s quite fun, in a slightly dark way, whilst it remains a thought experiment. But what should the AI-controlled, self-driving car do? What happens when ethical dilemmas are applied in real life?

These trolley scenarios are asking us to make ethical decisions, to form value judgements. In this case to choose the least worst option. Typically we’re then driven towards a utilitarian approach – how can I work for an outcome which helps the most people. The problem is that some still get run over – it wasn’t good for them.

A harder question, might be to consider how we manage competing goods. Choosing between outcomes which on the face of it are both ‘good’, in that no one gets run over now, but indeed might have unforeseen consequences.

If we can envisage that AI has the potential to radically transform society, at an industrial revolution type level then we need to get it right. There is an existential need and ethical imperative for the effects to be good.

But I fear utilitarian or situational approaches to the question of goodness will fall short. We have an alignment issue – not only getting the machines to align to our goals, but as a society being aligned on what our goals are – what would ‘good’ look like?

It seems to me a good thing to be able to live in a society without crime, but how should I weigh that against the value of personal privacy? I suspect we might think the Chinese ‘social credit’ system is unbalanced in favour of crime prevention.

A Christian theological approach is not a simple approach, it doesn’t assume that every ‘good’ can just be measured and metricated – real life is more complex than that.

But where it will perhaps differ and become a strong countervailing power, is in its inherent bias. A Christian approach will deliberately privilege the marginalised and excluded, it will challenge injustice and exploitation, it will genuinely seek what is good for ALL.

Can change be good, if it is not good for all?

Can change be good, if unforeseen harms result, and how do we determine the balance?

Can change be good, if the ‘goods’ disproportionately favour the powerful?

If we do nothing else, let us resolve to work to see AI used for the good of all people.

‘The Christian and Technology’ by John Fesko is an attempt to do that, a pastoral approach to technology, helping Christians to be thoughtful and considered in their use of technology. Fesko is clear from the outset, this is a ‘devotional book’ original based on a series of chapel lectures, indeed this certainly feels like a pastor warmly speaking to his flock.

‘The Christian and Technology’ by John Fesko is an attempt to do that, a pastoral approach to technology, helping Christians to be thoughtful and considered in their use of technology. Fesko is clear from the outset, this is a ‘devotional book’ original based on a series of chapel lectures, indeed this certainly feels like a pastor warmly speaking to his flock.